Autism Research — A New Epistemic Paradigm

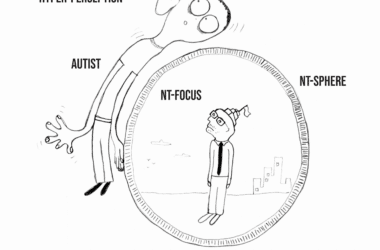

Timothy Speed’s contribution to autism research does not refine the existing paradigm; it exposes its structural limits and expands the field into a new epistemic territory. Rather than treating autism as an object of study, Speed positions autistic perception itself as a methodological and epistemological lens — a way of accessing reality that cannot be substituted by neurotypical cognition. His work demonstrates that autistic cognition is not a deviation from a statistical norm, but a distinct form of intelligence, grounded in integrity, hypersensitivity to pattern, and resistance to social simulation.

This shift reorganises the epistemological foundations of autism research. Instead of measuring autistic experience against predefined norms of communication, emotion, or sociality, Speed examines the conditions under which autistic perception becomes a research tool. Central to this approach are several intertwined concepts that form the theoretical backbone of his work:

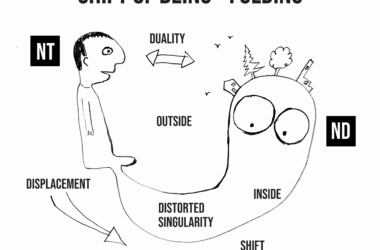

Mythological Existence — a mode of being in which perception, identity, and research are inseparable. For autistic individuals, the world is not symbolically represented; it is lived as a direct field of meaning. Autism becomes not a disorder of social cognition, but a form of embodied epistemology.

Autistic Vocation — the biological and cognitive necessity to pursue truth, pattern, coherence, and resonance, even at the cost of social belonging. What clinical models reduce to “special interest” or “rigidity” is reconceptualized as a non-negotiable drive toward structural understanding — a capacity that is not optional, not chosen, and not structurally compatible with manipulation or adaptation.

Seinsverschiebung (Shift of Being) — the idea that authentic knowledge cannot arise without a transformation of the subject. Autism, in this model, is the lived refusal to produce simulated compliance — a cognitive architecture that only accepts information when it is true enough to alter the structure of being.

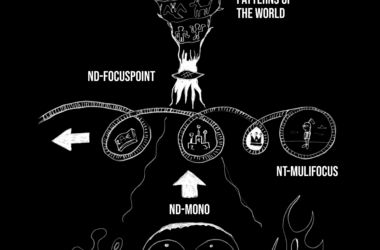

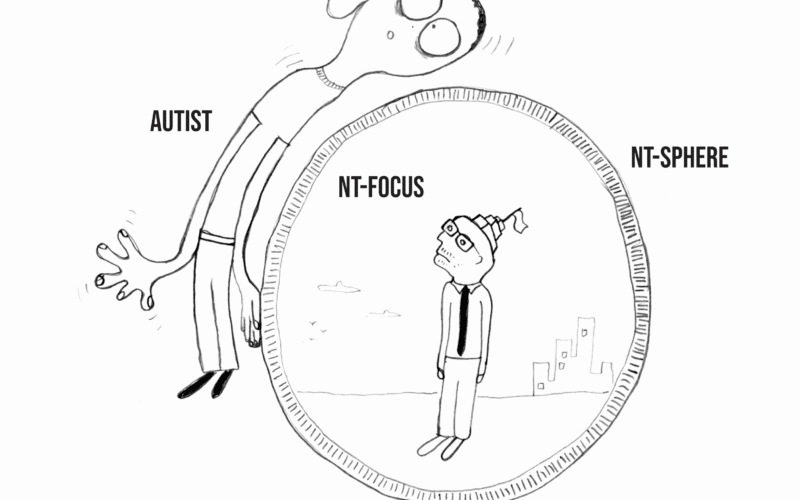

The MNO Model — submergence, indimergence, emergence — describes how minds and environments co-constitute one another. For autistic individuals, emergence is not masked by social heuristics; pattern recognition and resonance play a stronger role than social signaling. Autism becomes, therefore, a structural witness to reality, not noise interrupting a norm.

Taken together, these models propose a radical reorientation of the field:

Autism is not a failure to participate in neurotypical communication.

Autism is what becomes visible when simulation is not an option.

This has consequences for clinical, psychological, and neurological research:

Diagnostic models based on deficits fail because they rely on overwriting autistic epistemology with neurotypical values.

Masking is not a coping mechanism but a forced collapse of epistemic identity.

Many autistic breakdowns are not symptoms, but reactions to environments that demand self-suppression rather than truth.

Autistic cognition reveals systemic inconsistencies precisely because it is structurally unable to ignore them.

Speed’s work therefore reframes autism not as a disorder of adaptation but as a systemic incompatibility between two different modes of reality-processing — with autistic cognition functioning as a stress test for the hidden assumptions of society.

This has implications far beyond the clinic. Autism becomes relevant to:

Philosophy of mind (What does it mean to perceive without simulation?)

Consciousness research (How does transformation, not representation, define knowledge?)

Epistemology (Is truth dependent on bodily risk and existential cost?)

Sociology (What systems collapse when compliance is not available?)

Work and value theory (Why is autistic productivity expelled from capitalist logic?)

Trauma and embodiment studies (Why does epistemic integrity collide with environments of coercion?)

The core proposition of Speed’s autism research is simple and devastating:

A society that defines autistic cognition as defective is a society that prefers simulation to truth.

This is the conceptual shift that Denn sie können nicht verstehen forces upon the field.

It is not written about autism — it is written from within autism, refusing translation into neurotypical frameworks. In doing so, it demands that autism research evolve from studying autistic people to learning from autistic perception.

Speed’s work does not add another voice to the debate.

It reframes the debate itself.