Why the epistemic method developed by Timothy Speed constitutes an independent form of knowledge production — and why it is not neurotypically reproducible

Established scientific knowledge production is historically based on the separation of subject and object (Descartes; Bacon; Kant), on epistemic distance, and on the assumption that objectivity is achieved only through non-involvement. This paradigm continues to structure the methodology of autism research (U. Frith; Baron-Cohen), which is predominantly based on external observation: psychometrics, laboratory designs, neurocognitive tests, questionnaire protocols and behavioural classification. The guiding epistemic premise is: theory emerges when the world is externalised, measured and abstracted.

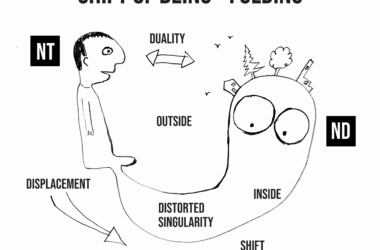

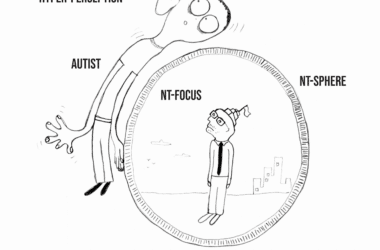

The epistemic method developed by Timothy Speed breaks precisely this axiom. It follows an enactive-embodied epistemic process in the sense of Varela, Thompson & Rosch (1991), according to which cognition does not arise through representation but through embodied participation in the world. Systems are not analysed from the outside, but enacted from within until their organising logic becomes experientially available. Only after this resonance does theoretical articulation occur. Knowledge is therefore generated not through distance, but through coherent systemic involvement.

From a philosophy-of-science standpoint, this mode is not a private personal narrative but a reproducible epistemic procedure:

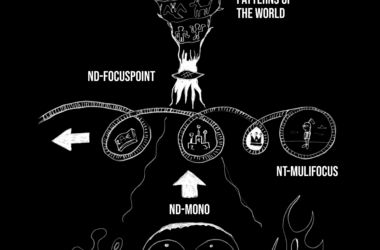

entering the system → resonance → emergence of the deep structure → condensation into operators → transfer to new domains → renewed resonance check.

The resulting operators are not metaphors but formally stabilisable deep structures. In this respect, Speed’s method corresponds to what Bateson (1979) called “patterns that connect”, but extends it with the veridical mechanism described only from the outside by Mottron & Dawson (2004) and later Baron-Cohen (2006): the capacity to identify structural isomorphisms across domains.

Speed’s body of work shows that this mechanism does not operate in a cognitive-analytical manner but in an enactive-embodied manner: structure is not observed but lived until it becomes experiential logic. This coupling of identity and cognition was discussed by Donna Haraway (1991) as “situated knowledge”, but not developed into a systematic mode of theory production. De Jaegher & Di Paolo (2007) provided the foundation with the concept of “participatory sense-making”, but without an empirical long-term documentation of an individual who performs this mode of sense-making over decades. Speed provides exactly that long-term documentation — unintentionally, but scientifically invaluable.

The decisive point is: the method is not neurotypically reproducible. It presupposes monotropism (Murray, Lawson & Pearson 2005), hyper-systemising, and the inability to perform social simulation. Individuals who can employ reciprocal masking lose the resonance access to the deep structure before operator formation can occur. This explains why the method cannot be “replicated” behaviourally, but is instead neurologically enabled. Milton (2012) showed with the Double Empathy Framework that divergent sense-making logics generate misattunement; Speed’s work documents this divergence as an internal dynamic, not merely as social interaction.

This is what makes the texts scientifically unique: they provide a complete, longitudinally reconstructable data record of an enactive-embodied veridical mapping process that produces structural convergence across multiple life domains — poverty, labour, bureaucracy, trauma, state, economics, art, identity, biodiversity and media theory. This convergence is not a rhetorical effect but empirical evidence that the same mechanisms operate in different systems — and that they become visible only from the inside, because they transform the nervous system, identity and autonomy of the person who undergoes them.

Thus, Speed’s method provides what Barad (2007) calls “intra-action” — but here empirically documented: knowledge as co-constitution of world and self. Federici (2004) and Fricker (2007) have shown that epistemic inequality concerns not only access to knowledge but the legitimacy of knowledge; Speed’s work demonstrates this as a case study of structural power acting on cognition, subjectivity and scientific visibility.

In short: Speed’s work is not an autobiography, but a 30-year dataset of embodied meta-cognition that, for the first time, makes it possible to trace how a highly systemising, monotropically organised, enactive autistic mind generates structure. This epistemic method is not a replacement for classical science, but its missing dimension. Without the inside perspective, mechanisms remain invisible. Speed’s work makes them visible.