ORDER AMAZON DE/EU

ORDER AMASZON UK

ORDER AMAZON US

ODER BARNES & NOBLE US

Timothy Speed – neurodivergent artist, poverty researcher and tireless troublemaker – places his skin, his mind and his camera between assembly line, boardroom and Jobcenter. As a Radical Worker he lives a work practice that is not oriented towards payslips, but towards ecological impact, moral coherence and personal meaning. His empirical interventions – from secretly working inside corporations to publicly applying to be director-general of the ZDF – reveal the hidden protocols of a system that turns dignity into profit and creativity into obedience. For the artistic-research community, Speed shows how artistic action becomes real infrastructure: here, art is not an illustration of critique, but the laboratory in which new forms of work and value are tested live. For Critical Autism Studies, the book provides a rare self-testimony: autistic directness, monotropism and rule-clarity become an analytical sharpness that penetrates institutional façades and makes alternatives visible. For all who have to work (or not work) it offers a radically practical roadmap: self-determined work, unconditional basic income and a commons economy are not only discussed, but tested in living field experiments. Speed upgrades the poor, defines forced labour as social isolation and introduces the “unfolding distance” as a new measure of prosperity: how much real lifetime remains after all the system noise? Radical Worker is manifesto, field study and user manual at the same time – an invitation not only to criticise capitalism, but to rebuild it in a concrete way.

Scientific insight into Radical Worker by Timothy Speed

Introduction and overview

Timothy Speed’s book Radical Worker – On the Right to Self-Determined Work is a genre-crossing work that unites artistic practice, social analysis and philosophical theory formation. Speed – a neurodivergent artist, labour and poverty researcher – lives what he writes about and acts as a “Radical Worker” in self-experiment. In this manifesto and self-experiment at once, he infiltrates organisations – from the factory floor to the executive suite – and lays open the “hidden protocols” of the system “that turns dignity into profit and creativity into obedience”. Instead of orienting work primarily towards wages and exploitability, Speed practises a work ethic according to ecological impact, moral coherence and personal meaning. In doing so, Radical Worker not only offers a sharp critique of contemporary capitalism, but presents a “radically practical roadmap” for alternatives: self-determined work, basic income and a commons economy are discussed and tested in living field experiments. The book functions simultaneously as manifesto, field study and user manual – an invitation not only to criticise capitalism, but to rebuild it in a concrete way.

Already in its blurb, Radical Worker addresses several academic and artistic discourses. For the Artistic Research community, Speed demonstrates how artistic action can become real infrastructure – art as laboratory in which new forms of work and value creation are tested live. From the perspective of Critical Autism Studies, the work offers a rare autoethnographic testimony: autistic directness, monotropism (i.e. focused attentional interests) and rule clarity become, in Speed’s case, an analytical strength that penetrates institutional façades and makes alternatives visible. Beyond that, Speed epistemically upgrades marginalised groups such as the unemployed or the psychologically divergent in the sense of Disability Studies – he “upgrades the poor” and defines, for example, forced labour not economistically but as a form of social isolation, which means a shift of perspective on work and participation. Taken as a whole, Radical Worker can be read as an interdisciplinary contribution that interweaves artistic research, sociological structural analysis, political philosophy and neurodivergent perspectives on knowledge. In the following, the central contributions of the book for individual disciplines as well as its theoretical innovations and unique features are examined in more detail.

Significance for Artistic Research

Radical Worker is first and foremost a result of Artistic Research – that is, research through artistic means. Speed makes use of performative interventions: he appears unannounced as a “Radical Worker” in companies or institutions, secretly works along, applies publicly and with media impact for positions (for example as ZDF director-general), etc., in order to provoke real situations. These “empirical interventions” are understood as artistic experiments in which Speed is at once subject and object of the investigation. He emphasises the advantage of this approach “in which the individual, as trigger of the experimental set-up, is part of the experiment”, so that art, activism and research can be seamlessly connected. In such provoked empiricism – a deliberate bringing about of experiences – disturbance is used in a targeted way in order to gain new insights into work: Speed provokes, advises, inspires or frightens employees and managers in order to break up routines; the “disturbance and reintegration of experience” serves him as research method. He makes the often drastic consequences of his actions (up to legal conflicts or his own financial ruin) public and subject to social debate – for example with the provocative question: “Would you rather I sell gummy bears, or how are you now going to deal with the work I do?” This procedure explodes traditional roles: the artist here is not a neutral observer, but an actor in the field who initiates and documents real events.

With regard to Artistic Research, Speed thus demonstrates a unique understanding of method: art is not an illustration of theory, but becomes a medium of knowledge in its own right. The book shows how artistic action can pass over into infrastructure – art becomes the workplace, the rehearsal of a future society. This approach recalls Félix Guattari’s concept of transversality in art: Guattari postulated a transdisciplinary activism that connects art and politics, and himself served as a theoretical as well as biographical model for a transversal activist transform.eipcp.net. In a similar way Speed acts as a transversal practitioner – his art arises inside the social systems that it criticises. In contrast to purely symbolic institutional critique, he embodies an aesthetic practice as intervention in the daily life of capitalism. In this way, Radical Worker makes a contribution to Artistic Research by establishing new methods (such as field infiltration, life-art experiments) and blurring the boundaries between artistic performance and social reality. Artistic research here gains a political and ontological status: it becomes a form of world-making. Donna Haraway’s idea of situated knowledge, according to which knowledge is always tied to a location and a body, is reflected in Speed’s approach – his artistic research is situated knowledge won from embodied presence in the field. Art thus becomes indirectly scientific: it produces data, theories and models from first hand, in the “laboratory society”.

Significance for sociology

Radical Worker also offers rich material for the social sciences – in particular sociology and social philosophy. Speed provides an unsparing analysis of modern work societies, which can be characterised as both systems-theoretical and saturated with experience. He observes how macroeconomic structures shape individual experience, and conversely, how individual actions can have feedback effects on structure. His long-term self-experiments reveal mechanisms of exclusion and precarity: over two decades Speed has shown how state and economic structures systematically prevent forms of work that would be ethically and ecologically meaningful. In doing so, he takes up the relationship between individual subjectivity and social structure – a central theme of sociology. Speed argues, for example, that prevailing economic theory calls on people to forego self-unfolding in the belief that this will increase general wealth. This reflects a critique of the classical sociological notion of the individual’s sacrifice for the sake of society: Speed shows that such a sacrifice is in truth a fallacy that leads to alienation and inefficiency. Instead, he argues that individual experiences of injustice should become the starting point for a renegotiation of social relations.

A central sociological innovation concept of the book is the “unfolding distance” (Entfaltungsabstand). Speed defines this concept as a new measure for progress and prosperity: it measures “how much real lifetime remains after all the system noise”, that is, how large the free space for personal unfolding beyond mere survival is. Put differently: unfolding distance is the ratio between the effort that individuals must invest in order to participate in social progress and the real gain in quality of life that this progress offers them. Technical and economic progress is legitimate, according to Speed, only if it enlarges this unfolding leeway, instead of – as in contemporary capitalism often – even narrowing it. Here Speed ties into sociological debates about quality of life, reduction of working time and the “good life”. His unfolding distance recalls Hartmut Rosa’s idea of resonance: Rosa criticises that the modern “imperative of escalation” of capitalism piles up resources and options but leads to alienation – “life does not succeed because we are rich in resources and options, but because we love it”. Likewise, Speed demands that progress not be measured one-sidedly in growth rates, but in qualitative gains in freedom and time prosperity. This re-evaluation touches fundamental questions of sociology: what is social progress? How do we measure prosperity? Speed offers here an original approach that connects a lifeworld orientation (à la Habermas or Rosa) with structural thinking.

Another contribution to sociology lies in Speed’s observation of primary and secondary economy. He distinguishes a primary economy – the comprehensive social, cultural and natural ecosystem of human action – from the secondary economy, the formal market economy. The primary economy includes all those expressions of life, relationships and care activities that remain invisible in balance sheets (e.g. child-rearing, informal help, voluntary work). Speed shows that the secondary economy often appropriates the achievements of the primary economy by, for instance, taking unpaid care work for granted. In contemporary sociology of work this is highly relevant: discourses on the upgrading of care work, on commons and on post-growth-oriented economies find theoretical substantiation here. Speed argues that the value of human beings and their work must be placed above the value of commodities – a perspective that would have far-reaching consequences: production would be reduced in favour of a life according to individual needs; diversity and sparing use of resources would increase. This vision of a humanised economy stands in the tradition of sociological utopia debates, but Speed’s approach is unusual insofar as he underpins it empirically: he has practically tried out parts of this vision in small experiments (such as community-supported agriculture projects, experiments with gift economies, etc., as described in the book). With this, Radical Worker provides sociology with a laboratory example for themes such as precarity, social exclusion and participation. Judith Butler has analysed precarity as politically produced vulnerability of certain groups – e.g. that the unemployed, disabled or marginalised are less respected and protected. Speed brings this precarity vividly before our eyes by placing himself in the precarious position (living in poverty, confrontation with authorities) and documenting social reactions. He unmasks the stigmatisation of the “useless” and shows that social isolation functions as a control mechanism – a finding that echoes Butler’s theses that precarity is a means of disciplining and devaluing life.

Finally, Speed updates the sociology of the subject: he propagates a new type of worker – the “Radical Worker” – as role model of a resistant subjectivity within late capitalism. This worker refuses the logic of profit and competition and instead follows an intrinsic orientation towards meaning, even at the risk of receiving no wage for it and being punished by the “market”. Speed’s own life embodies this model (up to exclusion and persecution by institutions). From a sociological point of view, this illustrates the scope and limits of action of deviant actors: what chances does individual refusal have in a normative constellation? Speed shows the lines of conflict – e.g. his conflict with the federal government over the future of work – and thus reflects agency vs. structure in concrete form. Overall, Radical Worker offers sociology new concepts (unfolding distance, primary economy), vivid case studies on precarity and social protest, as well as an impulse for the democratisation of work: Speed argues that work is “the essential action in society” and must therefore be democratised in order to make genuine diversity and freedom possible. This demand is in line with current sociological debates on economic democracy, but at the same time – through Speed’s life practice – shows the difficulties and potentials of its implementation.

Philosophical perspectives

Political philosophy and social theory

Speed’s work has a strongly normative and political dimension, through which it makes important contributions to political philosophy. Central is his plea for self-determination and autonomy in work – ultimately a call for freedom in the sense of a fulfilled human form of activity. Here one can draw a parallel to Hannah Arendt’s vita activa: Arendt famously distinguished between labour (mere maintenance of life), work (creative world-building) and action (political, free interaction). Speed now demands that the sphere of work be detached from necessity (mere labour for survival) and be turned into a field of meaningful activity and co-determination – in a sense, to translate work into the political (in Arendt’s sense). By emphasising self-determination and individual meaning as the core of work, he elevates work to a practice of freedom that serves both the individual and the community. This recalls Arendt’s demand that people must “actively influence and shape the world in cooperation with others” instead of remaining in routinised duty-fulfilment. Speed’s Radical Worker is essentially a proposal to grant every person the right to shape their work as a self-chosen, political action – as a contribution to the community that draws from freedom and diversity. Connected to this is the critique of the existing work ethic: success, for Speed, is not measured in money or status, but in moral coherence and social relevance. This revaluation has ethical and political explosiveness: it calls into question the prevailing meritocracy that equates market success with value. Instead, Speed ties into principles of a work ethic of responsibility, as are discussed, for instance, in the wake of Hannah Arendt or also in contemporary debates about “bullshit jobs” (David Graeber) – namely the idea that real work is that which has meaning and benefit for others, and not that which only serves profit.

Politically, Radical Worker demands concrete reforms that can be philosophically justified: the introduction of an unconditional basic income, for example, Speed grounds in the right to self-determined activity and as a means of overcoming the fear of poverty – “the only lever that capitalism still has”. In doing so, he intervenes in the political philosophy of justice (cf. debates on basic income by Philippe Van Parijs, on capabilities by Amartya Sen/Martha Nussbaum). His support for a commons economy likewise has philosophical points of reference: it aims at a reintegration of the economy into the social and ecological, which is reminiscent of demands made by thinkers like Elinor Ostrom or also by theories of ecological justice. Speed underpins this with the concept of the primary economy (see above), which philosophically redraws the boundary between economy and lifeworld – in the sense of an ecosophy as, for example, Félix Guattari sketched it in The Three Ecologies. Guattari emphasises that politics and culture must ultimately be ecological practices that concern the whole of life transform.eipcp.net. Speed argues in a very similar way: for him, self-determined work is not egoistic, but “ecological in an extended sense, since it encompasses human beings, environment and universe”. He demands an economy that functions as an ecosystem in order to enable diverse life forms – a genuinely political-philosophical vision that goes beyond conventional liberalism or socialism.

Remarkable, too, is Speed’s critique of power. In his interventions, he reveals the hidden power-protocols of institutions: how authorities react to uninvited participation (mostly with exclusion), how the power to evaluate is used to stamp people as “worthless”, or how fear of social decline keeps people compliant. Here, a kinship with Foucault’s analyses of power shines through, but from the internal perspective of the subjugated. Speed states that in the world of work, isolation and competition are deliberately used to increase productivity, but at the cost of quality of life and genuine creativity. In its current form, work is often only a “mechanism of aggressive goal-direction of life-force” that burns people out. This diagnosis is philosophically relevant because it raises the question of a good life under conditions of capitalist rationality – similar to, for example, Axel Honneth’s theory of alienation or Rahel Jaeggi’s critique of forms of life. By simultaneously practising alternatives, however, Speed brings a utopian-practical dimension into the philosophical debate: he does not remain at critique, but tests how a life beyond alienated work can look (e.g. by running community gardens, initiating open workshops, etc., as reported in the book). In this ultimately lies a political vision: a society in which every human being has the permission and possibility to do what they consider meaningful – and in which such work of meaning is carried collectively. This vision shares much with anarchist and grassroots-democratic theories (keyword prefigurative politics), but Speed does not formulate it abstractly, rather as experience. In this way he contributes to a philosophy of praxis, in the spirit of theorists like Paulo Freire: Freire’s concept of conscientização – critical awareness built through reflected action – is mirrored in Speed’s approach. He learns through action and teaches through his example, which recalls Freire’s idea that the oppressed themselves must become protagonists and teachers of their liberation.

Philosophy of mind and epistemology

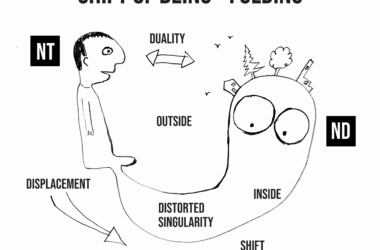

Besides the social-theoretical aspects, Radical Worker also has a distinctly philosophical-epistemological and philosophy-of-mind slant. Speed describes his research himself as a “radically embodied theory”. This phrase points to the fact that he does not gain knowledge through detached thinking, but through physically lived experience. In fact, Speed thereby takes up a strand in philosophy of mind: the theory of embodied cognition. Here a comparison with Francisco Varela’s concept of enactivism is particularly fruitful. Varela postulates that cognition is not the representation of a given world in the brain, but the “enacting” (bringing forth) of a world, depending on our sensorimotor action. In other words: living beings co-construct their reality in direct interaction with the environment instead of merely passively mapping it. Speed follows exactly this idea methodically: he “folds himself into the world, lives in it as in an open laboratory”. His insights into consciousness, reality and power arise in actu – by performing certain actions and observing the resulting resonance. In this way, Speed shares the enactivist basic idea that knowledge is situated and interactive. Also from an epistemological point of view, Speed’s approach fits this context: he questions the usual subject–object separations. In Donna Haraway’s sense of a “partial perspective” he emphasises that his thinking stands “crosswise to the mainstream” and springs from the specific perspective of a neurodivergent subject. Instead of claiming universal objectivity, Speed offers situated knowledge from the position of the “other” subject – which Haraway has proposed as a feminist ideal of science (knowledge that reflects its own positionality, instead of the supposedly neutral “God-trick” of objective science).

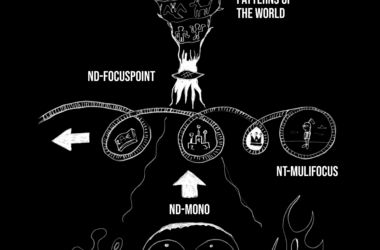

A particularly striking novel concept that is developed in Speed’s book at the intersection of ontology and epistemology is the MNO theory. MNO stands for “Minimal–Non–Object”. This model is Speed’s attempt to bring non-locality (from physics), subjectivity (from philosophy of mind) and social order (from sociology) onto a common denominator. Put simply, Speed suggests that the emptiness between things – that which is not present as a tangible object – is constitutive for reality. Reality consequently does not consist primarily of isolated entities, but of relations, of gaps, of the indeterminate that lies between objects and persons. Speed formulates this abyssal idea provocatively in questions: “What if reality does not consist of things but of what is missing between them? What if we are only the answer to a void?” Philosophically, this is reminiscent of approaches such as Buddhist concepts of emptiness or also certain interpretations of quantum theory (where the vacuum, the field, is more important than the particles). Speed’s MNO theory is presented in the book as a philosophical-physical principle that challenges conventional assumptions about reality. In physics, Speed claims, MNO could help to describe paradoxical states (one thinks of quantum entanglement, non-locality, etc.) – an order beyond space-time and particle logic in which each particle is only representational of MNO but never MNO itself. In the humanities and social sciences, MNO implies that perception and order change as soon as the non-objectual is included. The model undermines established dependency structures and allows paradoxes as fundamentally human – for example the coexistence of unity and diversity, of individual and collective, without forcing them into hierarchical dichotomies. MNO thus demands a redefinition of social design by recognising the seemingly absurd or empty as creatively potent. Speed even claims that MNO paves the way to an alternative understanding of freedom and unfolding – both individual and collective. Here he moves on highly speculative terrain: it is about the epistemic foundations of our conception of reality. His question “What does that mean for our […]?” (in the quotation truncated, but in sense: “…for our concepts of knowledge, of being?”) shows that he is aware of shaking the foundations. Even if the MNO theory in the book remains more of a visionary draft, it points to Speed’s uniqueness: he tries to bring subjective experience, philosophical ontology and systemic social theory into harmony. In this way he creates an interdisciplinary discourse space such as perhaps radical thinkers like Félix Guattari or Gregory Bateson (Steps to an Ecology of Mind) had in mind. MNO stands conceptually across from common schools of thought – it demands a thinking in gaps, relations and paradoxes. For philosophy of mind this is a stimulus to rethink the relationship between consciousness and world: consciousness not as closed substance, but as resonance in a between-space. This places Speed’s approach close to more recent phenomenology and posthuman theory, which understand subject and object, self and world as relational.

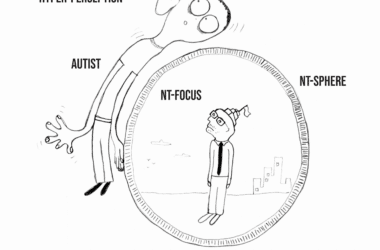

Finally, the neurodivergent perspective should be mentioned as a philosophical added value. Speed is an autistic person with ADHD; he openly reflects on how his atypical perception and cognition influence his formation of theory. Thus, for him, monotropism (the tendency to focus attention strongly) becomes a methodological virtue: through autistic focusing and adherence to rules he achieves an almost laser-like analysis of social situations. Instead of seeing his neurological difference as a deficit, he makes it into an epistemic resource – which, in philosophy of mind and epistemology, provides an example of “neurodiverse epistemology”. This concept coincides with reflections in Critical Autism Studies which discuss the “double empathy” and mutual problems of understanding between autistic and neurotypical people: Speed uses his outsider’s perspective to make visible aspects that get lost in the “neurotypical” uniform mass. Philosophically, he thereby embodies a different cogito: a thinking subject that does not correspond to the Cartesian, abstract-universal ideal, but is equipped with specific cognitive dispositions. The book opens space to ask what epistemic value autistic modes of thinking have – for example the emphasis on logical consistency, perception of detail, directness. Thus it contributes to a pluralistic epistemology in which different mind types provide interwoven, complementary insights.

In summary, Radical Worker offers philosophically an epistemological paradigm proposal: knowledge production through radically embedded, subjective practice. It demonstrates embodied knowledge in pure form and builds bridges from experience to theory. In Speed’s solitary path one can recognise echoes of Paul B. Preciado’s autotheoretical method: just as Preciado in Testo Junkie used his own body as a “body-essay” and took testosterone as performative act to analyse the regime of gender and biopolitics, so Speed uses his body and his life to illuminate the regime of work. Both embody philosophical theses through self-experiment – Preciado on gender, Speed on work. That is “theory in the first person”, which is still unusual in academic philosophy, but is gaining in importance. In this way, Speed lines up with the tradition of those philosophers who merge life and thinking – one might think of Diogenes, of Montaigne or of Simone Weil (who became a factory worker in order to understand work). Radical Worker provides here a contemporary example of radical life philosophy.

Significance for Disability Studies and Critical Autism Studies

For Disability Studies and specifically Critical Autism Studies, Speed’s work is of particular interest because it illuminates intersections of disability, neurodiversity and work. Firstly, the book is an autobiographical-theoretical testimony of an autistic person about his struggle with the demands of the neoliberal world of work – a perspective that is rarely documented so unabashedly. Speed describes from first hand how ableism and capitalism interlock: the unwillingness or inability to adapt seamlessly to the norms of efficiency and hierarchy leads to social ostracism. He experiences on his own body the pathologisation and criminalisation of “not functioning”. At the same time, however, he turns the tables by saying: it is not I who am deficient, but the system that is irrational. This approach reflects precisely the core of Disability Studies, which understand disability as a social construct and problem of the environment, not as an individual “affliction”. Speed demonstrates this drastically: by defining, for example, forced labour as social isolation, he shows that the problem is not unwillingness to work, but the society that pushes people without wage work to the sidelines. In doing so, he provides empirical material for theories such as Robert McRuer’s Crip Theory. McRuer argues that neoliberal capitalism establishes “ability” as a compulsory norm – it is taken for granted to be healthy, productive, available; otherwise one is excluded. Speed confirms this thesis and goes even further: he resists the compulsion to able-bodiedness by bringing his own “non-conformity” offensively into play and formulating it as the starting point for new appreciation. For example, he shows scenes in which he, as an autistic person, clearly names abuses and is sanctioned for it – which in the book appears as a moment of truth, not as misconduct. Here it becomes clear what McRuer calls “cripping”: the subversive reinterpretation of disability as something that bursts normative assumptions and opens up creative futures. Radical Worker is, in this sense, a “crip manifesto”: it sketches the vision that “disability” and otherness are no longer stigmatised, but that our vulnerable, dependent lives are fundamentally organised differently – “where care and support are joy rather than duty and disability perhaps becomes the norm and normality the exception”. Speed does not formulate it exactly like that, but his practical proposal (basic income, commons) aims precisely at this: a society that reckons with diversity, dependencies and atypical life designs and sees them as value.

Secondly, the book contributes to Critical Autism Studies (CAS) by taking autistic cognition seriously as an analytical tool. CAS demand that autistic voices and perspectives be included in science and that deficit narratives be questioned. Speed provides a prime example of this: he shows how autistic characteristics (monotropism – intense interest; directness – “saying what is”; rule orientation – sense for justice and structure) become, in the right environment, social-critical virtues. His analytical sharpness is explicitly attributed in the blurb to these neurodiverse features. In this way he offers empirical evidence for the CAS basic idea that autism should not only be examined from the outside, but that autistic people themselves are knowledge producers with a unique view. Speed is researcher and “research object” in one – he practises autoethnography as an autistic person. This corresponds with newer approaches such as the “双重 Empathie” problem (double empathy), which says that problems of understanding between autistic and non-autistic people are mutual. In his book, Speed conveys something to both sides: he explains to readers how he experiences the world, and at the same time he explains to the “neurotypical world” what, in his view, is wrong with it. It is precisely this that makes the book so valuable for CAS: it fills abstract theories of neurodiversity with lived experience. Beyond that, Speed also touches on questions of intersubjectivity: in one of his essays (linked on his website) he speaks about autistic intersubjectivity, that is, the way in which he, as an autistic person, experiences relationships and language. Such reflections flow implicitly into Radical Worker when he describes, for example, how he communicates in companies and where misunderstandings arise. From this CAS can derive insights into how institutions could become neuroinclusive – or why they have not been so far.

Thirdly, the book is also politically relevant for the disability movement. Speed connects the demand for a new work culture with disability rights without explicitly labelling it as such. Yet implicitly he demands the right to work differently – which is essential for many disabled people (keyword: reasonable accommodation at the workplace, flexible models, abolition of the compulsion to the “performance norm”). By describing his failure in rigid work structures and living alternative forms of cooperation, Speed provides arguments for more inclusive forms of work. This fits with current disability-studies discourses that ask how the world of work and social policy would have to be structured so that chronic illness, psychological diversity and physical limitations are not excluded. Speed’s proposals (basic income as security, commons as flexible net) overlap with demands of the disability movement for social security and community support independent of employment status. In addition, Speed’s person embodies the intersection of class and disability (poor and autistic): this double perspective is still underexposed in research, but is becoming increasingly important, since many disabled people are disproportionately threatened by poverty. Radical Worker shows how classism (contempt for the poor) and ableism (contempt for the “unproductive”) reinforce each other – and, in contrast, provides a positive vision of appreciative difference. The book thus offers points of connection to concepts such as “neuroqueer feminism” or “crip economics”, which try to rethink economy with the experiences of the marginalised. bell hooks’ idea that precisely the margins can be places of radical openness and creativity is confirmed here – Speed uses his marginal position to generate something new. And like hooks or Freire, he also emphasises the role of education and change in consciousness: the book has an emancipatory educational claim, it wants to empower readers to see their own situation critically and to recognise spaces for action (a parallel to Pedagogy of the Oppressed). In this sense, Speed also contributes to activist knowledge production, which is becoming ever more important in Disability Studies: creating knowledge not only about those affected but for and with them in order to bring about social change.

In sum, Radical Worker expands Disability and Neurodiversity Studies by a vivid example of an “insider” who generates theory through practice. It is a plural work – on personal, theoretical and artistic levels – that shows how vulnerability can be transformed into resistance. For academic as well as activist engagement with disability it provides both narrative (life story) and analysis and vision. The emphasis on care, meaning and commons as new guiding values of a work society in particular ties in with disability-justice approaches that demand an economy which affirms dependencies and places care at the centre. Speed’s work underpins such demands through a radical experiment that bursts the usual categories – exactly what Critical Disability Studies aim at: “to examine dominant assumptions of the social world and to bring diffuse bodily experiences into otherwise restrictive structures”. Radical Worker fulfils this by feeding Speed’s diffuse bodily experience into theory and public discussion.

Positioning in the landscape of art and science: parallels and reference points

Timothy Speed’s Radical Worker stands in fertile dialogue with numerous currents in art and science. His work can be comparatively positioned by drawing parallels with other theorists and artists:

Donna Haraway – Speed shares with Haraway the will to break with traditional boundaries and to use positionality as a strength. Haraway’s concept of situated knowledge says that all knowledge arises from a specific vantage point and precisely thereby can be honest and powerful. Speed practises exactly that: as a neurodivergent “troublemaker”, he gains new insights from his particular situation. Just as Haraway, in her Cyborg Manifesto, mixed science, politics and fiction in order to describe a hybrid subject, so Speed creates with the “Radical Worker” a hybrid figure between art figure, researcher and activist. Both work with a manifesto character: Radical Worker can indeed be read as a manifesto of a new worker subjectivity – comparable to Haraway’s Manifesto for Cyborgs, which sketched a new political identity. Beyond that, Speed’s turn towards relational thinking (MNO as model of the in-between) recalls Haraway’s later ideas (keyword “making kin”, the emphasis on connections beyond categories). Both Haraway and Speed call hegemonic dichotomies into question – such as nature/culture, subject/object (Haraway) or work/non-work, normal/deviant (Speed) – and playfully-provocatively sketch new understandings of these relations.

Paul B. Preciado – As already mentioned, Speed stands methodically in a line with Preciado’s autotheory. Preciado’s Testo Junkie (2008) combined personal transgression with theory: Preciado took testosterone and at the same time wrote philosophically about the body in capitalism. This mix of self-experiment, diary and theory finds an echo in Radical Worker. Speed “writes what he lives and lives what he writes”, just as Preciado turned his own flesh into text. Both works are radically transdisciplinary: Preciado combined gender theory, biology, psychoanalysis and politics; Speed unites the economics of work, sociology, neuropsychology and ethics. There are also content overlaps: Preciado coined the term “pharmacopornographic capitalism” to criticise the intertwining of pharmaceutical industry, technology and control over bodies. One could analogously attest to Speed a term like “psycho-economic capitalism” – he criticises how economics intrudes into the psyche (fear of social decline as motor) and how, conversely, psychic norms (obedience, adaptation) support the economy. Both authors use their body as stage of the political. Where Preciado writes that Testo Junkie is a “body-essay”, an essay written with the body, one could call Radical Worker a “work-essay” – an essay written with one’s own work. Preciado and Speed also share narrative openness: a bastard of memoir and theory that some may dismiss as non-academic but that precisely thereby opens new paths to knowledge. They pioneer a kind of “auto-theory” (as it is now called) in which the boundaries between scholarly treatise and personal narrative blur.

Hartmut Rosa – As a contemporary sociologist, Rosa has generated broad resonance with his theory of resonance. Speed and Rosa both diagnose alienation in late modernity through acceleration and instrumental rationality. Rosa’s critique of the “imperative of escalation” of capitalism finds its counterpart in Speed’s critique of the growth dogma that “demands ever more work and performance without increasing quality of life”. Both propose to think quality of life differently: Rosa with resonance (successful relations to the world), Speed with unfolding distance (space for self-unfolding). Basically both concepts aim at something similar – a countermeasure against quantity and tempo. Rosa says that a fulfilled life depends on being in tune with oneself and the environment; Speed formulates that progress should be measured by whether it “expands the life free-space above the life-necessary”, where “individualism, diversity and free will become possible”. That is Speed’s version of resonance. However, Speed proceeds more activist: Rosa remains in the academic sphere as analyst and exhorting theorist, while Speed takes action and attempts to create spaces of resonance in practice (e.g. community projects as “life laboratory”). One could say that Speed provides the micro-ethnography to Rosa’s macro-theory: he documents how people (himself and others in interaction) react to destroyed resonance and what happens when you try to step out of the rhythm. In this sense, Radical Worker complements the rather abstract “sociology of the good life” à la Rosa with a concrete report of experience and supplements Rosa’s philosophical reflections (towards new evaluation of time and relationships) with political demands (basic income, commons). Ultimately, both share the search for a new modernity that enables qualitative growth – Rosa theoretically as a “resonance society”, Speed practically as a “self-determined work society”.

Hannah Arendt – As already mentioned in the part on political philosophy, there are conceptual affinities with Arendt. Speed’s insistence on bringing plurality and novelty into the world of work (diversity of individual meaning projects as foundation of real democracy) mirrors Arendt’s appreciation of plurality in political action. He demands that work no longer be isolated duty-fulfilment, but contribute to the common world – analogous to Arendt’s concept of action, which shapes the world and creates memories. Moreover, Speed’s entire project is a struggle against social isolation – Arendt saw the destruction of social bonds and the isolation of individuals as a precondition for totalitarian rule. When Speed describes isolation as the worst punishment and as the essence of forced labour, he thus stands in this Arendtian tradition that links dignity with belonging and visibility. Interesting as well is Speed’s practice of speaking truth to power (he confronts managers with their lack of responsibility, tells authorities unvarnished what he thinks). This recalls Arendt’s concept of “truth and politics” – the idea that truthful speech in public is a courageous act that can shake power. Speed’s interventions are such courage to truth, albeit in unconventional settings. Overall, one can view Radical Worker as an attempt at a vita activa in the 21st century: the human being as active being who can make a beginning (Arendt’s natality) – Speed tries to initiate new things on his own within congealed systems. That he encounters resistance confirms Arendt’s finding how rarely genuine action is permitted in over-rationalised societies. Yet Speed’s persistence also shows the hope for freedom that Arendt drew from the mere fact of the birth of the new.

Félix Guattari – Guattari, as co-founder of schizoanalysis, pursued the vision of bringing about social change through altered desire and transversal practices. In many respects, one can see Speed as a kind of schizoanalyst of the world of work: he refuses the “usual” role in capitalism (similar to how Guattari’s schizophrenic patient refuses the normal subject role) and thereby makes immanent fracture lines visible. Guattari propagated a politics of micropolitical revolutions – small subversive acts that begin in everyday life and connect the three ecologies (mind, society, environment). Exactly this is what Speed does: his infiltrations are micro-revolutions in the workplace; they are meant to influence consciousness (ecology of the mind), social relations (ecology of the social) and the handling of resources (environmental ecology via primary economy) at once. Guattari also emphasised the importance of creativity and deviation against “Integrated World Capitalism”. Speed’s concept of “system-creative work” is directly compatible here: he offers “answers to the question of how an alternative to capitalism could look – a new economy based on authenticity and humanity”. This sounds like an echo of Guattari’s chaosmic future vision where new, heterogeneous orders arise. In Speed’s MNO model – the idea that paradoxes must be permissible as precondition for humanity – one can also recognise Guattari’s influence: Guattari loved paradoxes and non-linearities; he would likely have agreed with the idea that the non-objective, ungraspable can be an ordering force. Moreover, Speed’s whole biography – artist, activist, researcher in one person – is a lived example of what Guattari called “molecular revolution”: personal existence as field of political transformation. Guattari’s concept of the “third ecology” (the mental/aesthetic ecology) likewise finds a counterpart in Speed’s emphasis on subjective worlds of meaning as part of the economic system. Finally, compare the concrete form of action: Guattari, in psychiatry, worked to dismantle hierarchies (La Borde clinic, group therapy, etc.), i.e. to change institutions from within. In the same way, Speed goes into companies and authorities and attempts to “rebuild” them from inside. Both encountered resistance – but their approach of bringing a foreign voice into the interior of institutions is very akin. Thus Speed stands in a line with Guattari as a model of transversal, unorthodox acting that challenges the conditions both theoretically and practically.

Judith Butler – Butler has primarily worked on gender and political philosophy, but some of her concepts are transferable. Particularly precarity and performativity are relevant here. Speed is, in a sense, a performer – he performs the role of the “radical worker” in order to subvert normative expectations of “employees”. This performative act bears resemblance to Butler’s theory of performativity: by embodying a different kind of work, Speed shows that what counts as “normal work” is itself only a continuously performed social act that could be done differently. Butler’s idea that identities arise through repetition and that subversive repetition can change them fits well with Speed’s strategy of consciously setting himself against the scripts of work identity and playing something new. Even clearer is the connection via the concept of precarity: Butler describes precarity as the condition in which people are kept in uncertainty by social policy – lack of security, recognition and support leads to a vulnerable life. In Radical Worker, Speed provides a case study in precarisation: he shows how he is driven into poverty and subjected to enormous psychological strain due to his non-conformism (for example when he is sanctioned by Jobcenters, risks homelessness, etc.). In doing so, he substantiates Butler’s thesis that precarity is politically distributed – certain bodies/subjects are deliberately less protected. At the same time, however, he also exemplifies Butler’s implicit hope: that in the sharing of precarity (a common being vulnerable) lies political potential. Speed implicitly calls for solidarity with the excluded and for acknowledgement of general dependency (his model of a commons economy, for example, is based on the idea that everyone cares for one another because we are vulnerable). This thought coincides with Butler’s demand for a politics that does not deny vulnerability but tends to it. Finally, Butler emphasises the importance of assembly – precarious bodies that assemble and make themselves visible can move something politically (see Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly). Speed’s actions – from public Jobcenter protests to media events – are forms of such assemblies (even if at times he stands “assembled” alone, he makes precarious life visible). Thus Radical Worker demonstrates on a small scale what Butler analyses on a large one: the politics of making vulnerable life visible.

Robert McRuer – We have already discussed McRuer’s concept of compulsory able-bodiedness, i.e. the compulsion towards performance capacity that neoliberal societies produce. Speed provides a striking example of this and at the same time a counter-strategy. In Crip Times, McRuer asks how disability and austerity policy are connected globally and how disability activists generate resistance. Speed shows this connection on a micro-social level: by being impoverished and disabled (in the sense of “pushed to the edge”), he personifies the victims of neoliberal policies; through his actions (e.g. public confrontations, field experiments) he generates a form of resistance. In this sense he is a practical actor in what McRuer theoretically calls “crip resistance”. Particularly McRuer’s emphasis that we must reject neoliberalism because it both demands employability and deepens inequality is directly echoed in Speed’s book. Speed radically rejects the doctrine “those who do not work shall not eat” and shows that it is precisely this doctrine that destroys people. Instead, he tries to set disability/otherness as a starting point for change: where McRuer asks whether we can imagine a world in which disability is the norm and not the exception, Speed goes and lives, for moments, as if that were already the case – namely by giving himself work regardless of his “non-function”, advancing projects and insisting on being part of society. In this way, he fills McRuer’s call for “imagining disability futures” with concrete content. One can thus read Radical Worker as a case of a “crip utopia”: it demonstrates in outlines how community, economy and subjectivity could be organised differently if, instead of competition and fitness training (in the figurative sense), cooperation and acceptance of dependency were to take their place.

Francisco Varela – As a representative of the cognitive-scientific counter-movement to dualism, Varela (together with Thompson and Rosch) formulated an enactive view of mind and world in The Embodied Mind (1991). As already discussed, Speed’s embodied approach resembles Varela’s principle that “perception and action inseparably bring forth a world together”. Furthermore, Speed shares with Varela an interest in transcending fixed categories. Varela’s Buddhist-inspired question “Who is the I and how does it arise in dependence?” fits the implicit question in Radical Worker: who am “I” (Speed) within a large system, and can I change this system by changing myself? It is also interesting that Speed – like Varela – thinks interdisciplinarily (connecting physics, philosophy and cognitive science). His MNO model could be interpreted in a cognitive-scientific way: perhaps he means that our consciousness arises from a gap, a non-object structure – similar to how Varela argues that there is no homuncular ego, but an emergent phenomenon from many interconnected elements. Speed formulates differently (more poetically and system-critically), but in tendency he offers food for thought for an enactivist social philosophy: if we are part of the world we observe, we must also understand the economy as part of our consciousness – and can thus actively reshape it. This kind of pragmatic constructivism is also found in Varela, who saw meditation and ethical action as part of cognition. Speed does not meditate, but he practises a form of mindfulness in action – he goes right into situations in order to experience and understand them directly instead of relying on theories from outside. In doing so, he also contributes something innovative to the sociology of knowledge: he shows a method by which one can understand complex systems by living them through in first person. This is almost an extreme version of Varela’s first-person methodology (which the latter demanded for consciousness research). For current discussions on embodied cognition, Speed thus provides an example of how social knowledge can also be embodied. His work stands conceptually alongside such attempts as Helga Nowotny’s social experiments or Chris Kelty’s participant observation but goes further still by entirely dissolving the distinction between researcher and researched. Thus one can appreciate Speed (even if he perhaps does not cite Varela) as someone who applies enactive thinking to society.

bell hooks – The feminist thinker bell hooks emphasised that the margins of society are often the places from which new visions arise – “margin as a space of radical openness”. Speed literally lives at the margin (poor, misunderstood, outside “normal” career paths) and develops his critique and creativity precisely from there. This embodies hooks’ idea that the oppressed possess unique knowledge about society because they are located at the periphery. hooks is also known for combining theory and personal experience, especially around questions of class and racism. In Where We Stand: Class Matters she wrote about the regime of shame and power that goes with poverty – something that Speed analyses similarly in the German context (stigma of the “Hartz IV recipient”, etc.). hooks demanded that love and care be placed at the centre of radical politics (All About Love); Speed speaks more of commons and authenticity, but essentially it is also about a way of life shaped by empathy and genuine encounter rather than cold competition. He tells, for example, how genuine appreciation between people can only arise when one breaks out of market logic – a statement that mirrors hooks’ emphasis on community and love as practices of resistance. Pedagogically, Speed can likewise be compared with hooks: hooks’ Teaching to Transgress advocates education as act of freedom in which the experiences of marginalised students are central. Speed practises a form of public pedagogy by shock-teaching society. His provocative actions force his surroundings to take a stand and perhaps learn something (for example, his cases were discussed in the media – the book then serves as a debrief of these “lessons”). In this sense, Speed is, like hooks, a “teacher at the margins” who tries, by telling his story, to get others to think about class, work and justice.

Paulo Freire – Freire’s influence is indirect but tangible. Freire postulated that real liberation can only be achieved through the praxis of the oppressed themselves, through reflection + action (“praxis”) in their own life context. Speed has done exactly that: as someone economically oppressed, he has begun to reflect critically on his surroundings and, at the same time, has gone into action (he calls it field experiments). As in Freire’s literacy campaigns, Speed learns through his own doing and then formulates concepts that stem from experience (unfolding distance, etc.). Freire also believed in dialogue and consciousness building on equal footing. Speed seeks dialogue – he directly approaches managers, officials, colleagues and tries to draw them into a conversation about meaning and responsibility (even if this often fails). One can see Radical Worker as a contribution to popular enlightenment (in the best sense): Speed explains complex interconnections (e.g. primary economy, value barrier) in accessible language, interconnected with stories, so that laypeople can also understand where the problems in the system lie. This corresponds to Freire’s approach of “popular education” which de-elitises theory and brings it to the people. It is also interesting that Speed never denies the humanity of the “oppressors” – he does not vilify managers as monsters, but appeals to their responsibility, which recalls Freire’s stance that the oppressors too can be freed through dialogue (if they allow it). Finally, Speed shows along Freire’s lines that knowledge and power are connected: by appropriating knowledge (through secretly working in companies, studying laws, etc.), he empowers himself against authorities – exactly Freire’s concept of conscientização. In this sense, Radical Worker could be read as a kind of “pedagogy of work”: it teaches us to rethink work through the eyes of one who is excluded by the prevailing work order but does not remain passive.

These comparisons show that Radical Worker reaches into many debates of our time: from feminist epistemology (Haraway) via gender and queer theory (Preciado, Butler), social philosophy (Rosa, Arendt) to disability theory (McRuer) and educational thought (hooks, Freire). Nevertheless, Speed’s work is not a mere derivative of these ideas – it connects and translates them into a novel constellation. Precisely this makes up its unique features.

Epistemic, methodological, artistic and political unique features

Finally, the special characteristics of Radical Worker shall be clearly highlighted:

Epistemically: Speed delivers an original theory of knowledge from below. Here, knowledge is not gained through abstraction but through radical participation and self-involvement. This “radically embodied theory” bursts the frame of classical objectivity and instead establishes a personal-universal standpoint of knowledge: being-in-the-world as research method. He generates new concepts (unfolding distance, value barrier, primary economy, MNO, etc.) that are distilled from his experience and yet claim general validity. This synthesis of subjective perspective and structural-theoretical claim is epistemically unique. Moreover, Speed crosses disciplinary boundaries more boldly than many academics: he brings physics, philosophy of mind and social theory into a common model (MNO) – an epistemic creative achievement that is unorthodox but inspiring. He shows that processes of knowledge themselves can be politically and creatively shaped if one abolishes the traditional division of roles (researcher vs. researched).

Methodologically: Radical Worker demonstrates a unique combination of methods: Artistic Research + autoethnography + systems theory. Speed unites aesthetic practice (performance, intervention) with empirical social research (participant observation, experiment) and theoretical model building. He uses both qualitative methods (reports of experience, narrative reflection) and quasi-quantitative ideas (new metrics such as unfolding distance). The method can be described as “provoked empiricism” – the deliberate staging of situations in order to learn from them. This approach is unprecedented in its consistency; comparable approaches (Situationism, action research, etc.) did not go so far as to make one’s entire existence into a research instrument. Speed, however, makes his life into a laboratory – a method that carries high risks (personal hardship) but also yields high returns (deep understanding from within). Methodologically innovative as well is the communication of results: the book is not a classical research report, but a transdisciplinary review written in accessible form that simultaneously contains academic theses, personal stories and artistic elements (some passages are almost literary). This hybrid mode of writing is methodologically noteworthy because it addresses different audience segments – academics, activists, artists, laypersons – and thus performs transfer work. Overall, one can describe Speed’s method as “radicalised action research” in which researcher and action merge.

Artistically: As an artistic work, Radical Worker stands out because it conceives of art not as representation, but as real world-making. Speed shifts the boundary of what art can do: from symbolic critique to real intervention in systems. His actions – whether one calls them performance art, intervention or social sculpture – take place in “real life”, with an unprotected outcome. The book documents and reflects these artistic processes, which gives it a special place in the art world: it is at once artwork (in the sense of a conceptual project) and reflection on art as social practice. With Speed’s approach, the ideal of the avant-garde is realised anew: the abolition of the separation between art and life. He lives the role of the artist as social agent, comparable perhaps with Joseph Beuys’ idea of social sculpture, but more radical in its immediate confrontation. The book is also artistically marked by its language: Speed writes at times poetically, at times polemically, shifts registers, uses metaphors (for example the “bull in front of the Red Bull headquarters” as action) and thus creates a dense narrative. This oscillation between analytical clarity and artistic freedom makes the reading unique. Artistically, the authentic radicality must also be highlighted: whereas many artistic actions remain in protected spaces or ultimately become integrated into the art market, Speed refuses this – his art happens outside institutional galleries, and he himself remains poor instead of capitalising his radicality. This lends his work a credibility and urgency that have become rare in art.

Politically: Politically, Radical Worker is singular because it links theory and practice of change so closely. Speed is not content with formulating utopias – he tests them. He does not just demand basic income – he sometimes lives as if there already were one (by doing unpaid work and relying on solidarity, for example). His political demands – right to self-determination in work, recognition of informal work, redistribution of appreciation – gain persuasive power through his personal example. Politically challenging, too, is his uncompromising stance: he addresses taboos (e.g. he exposes hypocrisy when companies preach CSR but internally practise exclusion) and takes on powerful actors (lawsuits against administrative arbitrariness, etc.). In doing so, he is independent – bound to no party or organisation – which allows him to formulate a fundamental critique of the system that still offers concrete starting points. Unlike some academic leftists who criticise capitalism in the abstract, Speed shows tangibly where you could grab hold of it. Politically unique as well is his focus on dignity and meaning. Ultimately, he argues for a politics that gives people back the feeling of being useful and connected instead of pressing them into alienated jobs. This has a humanistic quality that goes beyond classical ideologies – it is neither strictly Marxist (class struggle recedes behind the drive of creativity) nor liberal (the individual is thought precisely in relation, not as an isolated entrepreneur of himself). Speed’s politics is one of empowerment and care at once: empowerment because everyone should be allowed to define their own work; care because he wants society to materially secure these free unfoldings (through commons and basic income). Thus he provides an integrated social blueprint that is highly topical in current debates about post-capitalism, care revolution and community-oriented economy. Finally, politically noteworthy is the courage to experiment that he propagates: he indirectly calls on readers to do as he does – to try things that lie beyond the comfort zone in order to find out how we want to live together. This invitation to participatory system transformation (instead of top-down revolution) is a fresh, democratic impulse.

Conclusion: Radical Worker by Timothy Speed is an exceptional work that sets new standards in its complexity and radicality. For Artistic Research, it demonstrates the power of artistic action as instrument of knowledge and change. For sociology, it offers new concepts and empirical insights into precarity, work value and social ecology. In philosophy, it stimulates reflections on freedom, subjectivity and reality beyond traditional dichotomies – with concepts such as MNO that place the in-between at the centre. For Disability Studies, finally, it embodies lived critique of ableism and shows the productive force of deviation. Across disciplinary boundaries, the book stands out through its pioneering spirit: it is manifesto, experiment and theory in one – a real thinking laboratory. Its unique features lie in the epistemic authenticity, methodological boldness, artistic efficacy and political vision that it unites. In this way, Radical Worker enriches the art and science landscape with a unique voice that encourages imitation as well as further development. It challenges established thinkers to look beyond the edge of their discipline and encourages activists to act with greater reflection – in short: it does exactly what an outstanding interdisciplinary work should do, namely open new spaces of thought and provide practice-relevant impulses. In a time in which crises of meaning in work, ecological emergency and social inequality are pressing problems, Timothy Speed’s Radical Worker offers a courageous, original and inspiring contribution to the search for other ways.